Spotlight on Research

Chad Walker

Chad Walker’s research sits at the intersection of the environmental social sciences and climate action, with collaborations spanning Canada, the UK, and Norway. His work explores how communities and governments negotiate energy transitions and sustainability through local environmental governance, renewable energy planning, and climate adaptation strategies. From Indigenous knowledge in water management to equity in rooftop solar adoption, Walker’s projects aim to make climate solutions both practical and inclusive.

For Walker, the societal impact of his research lies in answering real-world questions about climate change and clean energy. “Of course we want our research to have impact in academic settings and advance knowledge in that way,” he explains, “but we also need to make sure that knowledge is practical and accessible – helping to shape the short, medium and long-term goals that communities have.”

A central challenge uniting his diverse projects is what he calls “making it difficult for policy makers to make bad decisions.” By producing high-quality, globally relevant, and accessible research, Walker aims to guide policymakers toward pathways that support sustainable futures. His findings consistently highlight the benefits of locally driven climate action, noting that Indigenous and community-owned renewable energy projects lead to higher levels of social and political acceptance—critical for sustaining programs and policies over time.

Walker’s commitment to community-based research was shaped during his first postdoctoral position at Queen’s University, where he worked with Drs. Heather Castleden and Diana Lewis. There, he learned the importance of Indigenous-led research and Etuaptmumk (two-eyed seeing), which continues to inform his work on renewable energy and water knowledge practices and development.

Ultimately, Walker hopes his research helps people see that equity and participation are not optional in climate planning—they are foundational. Whether sitting in a living room listening to firsthand experiences or analyzing global case studies, his work underscores a simple truth: sustainable futures start with inclusive conversations.

Michael Faciejew

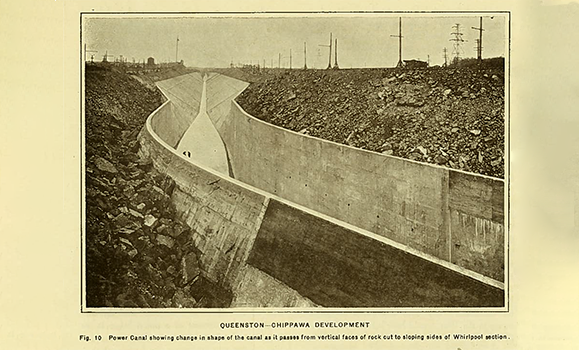

Photo Credit: Concrete-lined canal for the Queenston-Chippawa hydroelectric development in Southwestern Ontario, 1921. Published in Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario, “Official Opening of the Queenston-Chippawa Power Development on the Twenty-eighth day of December MCMXXI by the Hydro-Electric Commission of Ontario” (1921). Public Domain.

Michael Faciejew studies how architecture intersects with large-scale infrastructural, technological, and colonial systems. As a historian, he is particularly interested in how built environments have anchored political systems and how alternative futures can be shaped through design at multiple scales.

His SSHRC-funded project, “Terraqueous Architectures in Settler Colonial Canada” (2025–2027), looks at land, water, and power, and how the relationships among them have shaped Canada’s identity and environment since the 1867 Confederation. The research looks beyond buildings as static objects to reveal their role in resource extraction, energy production, and scientific exploration.

The project examines structures that negotiate land and water in unique ways, such as trading posts, hydro dams and powerhouses, tailings dams, and maritime research centres. Each case study tells a unique story. Hudson’s Bay Company trading posts, for example, were not just sites of commerce—they were part of a speculative real estate system that transformed land and water through property conventions. Another case study focuses on the Bedford Institute of Oceanography, a modernist complex built in 1962 in Dartmouth, NS, that advanced ocean research and climate science while symbolizing Canada’s push for environmental control, even in the Arctic, where fossil fuel exploration was accelerating in the postwar period. In each of the project’s four case studies, socio-political relations, at the scales of community and the state, are shaped by techniques of environmental design.

Faciejew’s work sheds light on how earlier “energy transitions,” like the move to hydropower in the early 20th century, which produced devastating environmental transformations, mirror today’s debates about electrification and renewable technologies. These histories reveal blind spots that persist in narratives of innovation and progress, such as the conflict minerals needed for solar panels, which are ubiquitous in the contemporary built environment.

Faciejew also challenges the way we think about architecture itself. It’s not just land-based—it’s “terraqueous,” spanning land and water. From port cities to offshore drilling platforms, these spaces expose the global entanglement of architecture, labour, capital and ecological change. His work draws on interdisciplinary collaborations and the scholarship of Indigenous and decolonial thinkers to reimagine Canada’s architectural heritage beyond identity tropes, toward a more holistic understanding of power, environment, and possibilities for recovery.